Freedom Wilson sketching a branch of blackberry (Hamish Dunlop)

By Hamish Dunlop

The Swamp Diaries is an initiative of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute. Over 12 months, artists are spending time with precious and endangered upland swamp ecosystems across the Blue Mountains and creatively documenting the flora and fauna they observe.

WARNING: A terrifying bunyip appears at the end of this story!

‘Apple Tree’ Swamp (Hamish Dunlop)

‘Apple Tree’ Swamp

I visit the former Katoomba Golf Course, where Freedom Wilson, coordinator of the Swamp Diaries, takes me to ‘Apple Tree’ Swamp. It’s the group’s colloquial description for the swamp because a single apple tree grows out of the reeds on the edge of the swamp where I imagine a core was tossed years ago. Freedom tells me about a natural spring, and I’m intrigued as she directs my eyes to a patch of bare earth in the middle of the fairway. We find water quietly bubbling out of the ground.

I wonder how the former Golf Course owners kept this area perfectly manicured with water trickling onto the green. I see other patches where water is finding its way to the surface. It’s an interesting metaphor for the resilience of natural systems.

The Swamp Diaries is part of the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute’s Eco-Art Space initiative. It provides a framework for artists and scientists to collaborate, generating new ecological knowledge. It also engages community to raise awareness about important ecological issues.

Recovery was another Eco-Art Space project that preceded the Swamp Diaries. It brought together ecologists, citizen scientists and artists to investigate the effects of the 2019/20 fires.

Xyris species (Fiona Vaughan)

Seed funding for Swamp Diaries was generated from SwampFest, a Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute fundraiser held at Katoomba RSL in 2022. The night raised funds, but also awareness about swamps and the need for swamp education in the Blue Mountains. Ian Wright, Professor in Plant Functional Ecology, gave a talk. Gundungurra elder David King also spoke, as did Holly Nettle, Swamps Project Officer with the Institute and Cadet, Environmental Science with Blue Mountains City Council. Artists donated works which were auctioned, raising enough to pay for artists’ supplies and exhibition fees.

COVID had limited many of the face-to-face elements of the Recovery project, pushing the workshops and exhibition online. One of the artists, Fiona Vaughan, focused on swamps. Freedom says that after Recovery wrapped up, Fiona kept saying she wanted to do a swamp project. “She’d see me and say, ‘When’s the swamp project going to happen?’ And I’d bump into other artists in the street, and they’d ask me, ‘When is it going to happen?’” With this encouragement, Freedom approached Sarah Terkes at the Institute, and the Swamp Diaries was born.

Upland Swamp Landscape (Fiona Vaughan)

The artists have each chosen a Blue Mountains swamp to spend time with and creatively document over the coming year. Their methods include photography, painting, drawing, sculpture and water quality testing. They’re hoping that what they uncover through their artwork will encourage others to become involved with these precious ecosystems. The project will culminate in a public exhibition at the end of 2023.

Why Swamps?

One question people ask is: ‘Why swamps?’ The first answer is that they are high in biodiversity. This is important because complexity in the web of life creates resilience. The second answer is that the health of our Blue Mountains upland swamps directly impacts the quality of our water.

Flame Robin near upland swamp (Fiona Vaughan)

Peat swamps grow slowly. Some Blue Mountains upland swamps have been forming over hundreds of thousands of years, a period that is also impossible to comprehend. In comparison, the length of a human life is like a rain drop falling from a leaf to the ground. Swamps accumulate peat, which supports plant and animal life, acting like giant sponges and water filtration systems. Healthy swamps have stable water tables, which filter through the peat, slowly releasing water downstream into catchments that supply the Blue Mountains’ and Sydney’s drinking water.

“Most of the world’s wetlands came into being as the last ice age melted, gurgled and gushed. In ancient days fens, bogs, swamps and marine estuaries were the earth’s most desirable and dependable resource places, attracting and supporting myriad species. The diversity and numbers of living creatures in springtime wetlands and overhead must have made a stupefying roar audible from afar. We wouldn’t know. As humans have multiplied to a scary point of concern about the carrying capacity of the earth, wetlands were drained and dried for agriculture and housing.”

Annie Proulx: Fen, Bog & Swamp (2022)

Wetlands were also drained to create golf courses.

The Blue Mountains is fortunate to have a Council that is committed to protecting swamps by managing polluting urban stormwater runoff with stormwater pits, biofiltration systems and rain gardens. Council is also keen to restore the peat swamp at the former Katoomba golf course.

But swamps are continuing to collapse.

Council has been working with the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute to negotiate with Transport NSW around widening of the Great Western Highway after the tragic collapse of the Bullaburra Swamp.

According to the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute: “The recent floods saw significant channelisation of the Bullaburra swamp, and the peat layer that formed over many thousands of years was washed away by the massive volume of water flowing into the area.”

Research identified that the Bullaburra Swamp collapsed due to run-off and contaminated water from the Great Western Highway.

Monitoring of the swamp water carried out … by Prof Ian Wright from the University of Western Sydney, in conjunction with the Blue Mountains World Heritage Institute’s Swamp Monitoring program, has shown that high levels of phosphorous and other trace elements leached from the concrete used in highway construction is making the swamp’s usually acidic water more alkaline.

https://www.bmwhi.org/news/2021/5/9/media-release-fears-for-iconic-bullaburra-swamp#:~:text=An%20iconic%20Blue%20Mountains%20Swamp,from%20the%20Great%20Western%20Highway.

The Artists involved in the Swamp Diaries

Artists at Apple Tree Swamp L-R: Cheryle Yin Lo, Justin Morrissey, Freedom Wilson, Caroline Giniunas and Fiona Vaughan (Hamish Dunlop)

The artists involved in Swamp Diaries include Freedom Wilson, Cheryle Yin Lo, Fiona Vaughan, Justin Morrissey, Caroline Giniunas, Ann Niddrie, Kate Reid, Emma Magenta, Rani Brown, Scott Marr, Wendy Tsai, Chia Moan, Brooklyn Sulaeman and Bryden Williams.

While they all have different practices and different reasons for getting involved, there is perhaps one common thread, beautifully articulated by Ann Niddrie.

As well as running a photography business for 20 years Ann also completed a degree in environmental science. When a lecturer asked her why she was there, she said she wanted to save the world. She laughs as she tells me the lecturer replied, “Join the club!” Ann says that what attracted her to the Swamp Diaries was the opportunity to connect with others and feel that collectively they could gently make a difference. “We are all curious and we are all exploring,” she says. “We want to share our discoveries with people and give them the opportunity to discover new things too.”

I had imagined that spending time in the swamps was something the Swamp Diaries artists did by themselves. I’m pleasantly surprised to find myself at one of the fortnightly meetings where some of the artists have come together on the grassy hill above the swamp.

It’s a beautiful sunny day. I’m offered biscuits, nuts and tea. There’s a generosity here, as the artists share their thoughts, talk about their practices and catch up with each other. Everyone tells me in their own way how important the community aspect is. They find that being part of a group who share common concerns, creates resilience.

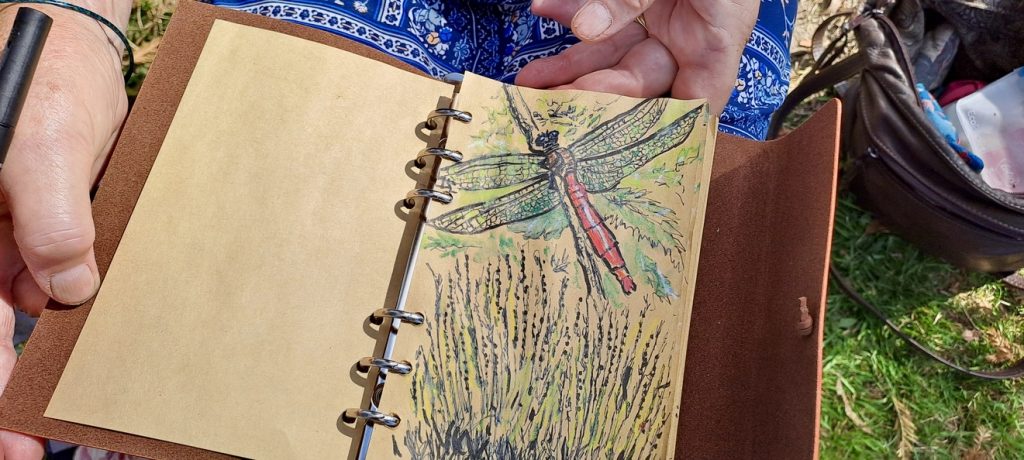

Dragonfly by Caroline Giniunas (Hamish Dunlop)

Freedom Wilson

Freedom’s main interest is vegetation and pollination. She is fascinated by the relationships between natives and weeds and fungi and plants. She’s been watching the seasons of flowers bloom and fade. She talks about her gratitude for living in the Blue Mountains: “It’s not like places where people look for inspiration on their phone. We just go for a walk. We walk out our back door. It’s wonderful.”

During lockdown, Kate Reid, who ran the Recovery project seminars, came up with the idea of ‘art-ercise’. Freedom says, “We’d go walking with one other person in the bush around where we lived, and we’d notice things and talk about what we saw.” While walking, artists drew, took photos, wrote poetry, made sound recordings and talked about what kind of artwork they were planning to make. Freedom says it really helped everybody, because “lockdown was depressing at times.”

Freedom Wilson at Apple Tree Swamp (Hamish Dunlop)

Freedom carefully works with her pencil now, capturing the form and essence of a blackberry stalk. “It’s a beautiful thing to do. A slow process that makes you focus on one thing at a time. It also allows you to really hone in on ecological relationships and try to understand how things work.” She says when you look at blackberry, it’s possible to just see the weed. When you start to draw, it becomes something else. The berries in different stages of ripeness come into focus. Sometimes the prominent veins on the undersides fork off the midrib symmetrically, but sometimes they are off-kilter.

Freedom Wilson observing blackberry (Hamish Dunlop)

Freedom tells me that Apple Tree Swamp became one of her swamps because she walks her dog there. At first, all she could see was the apple tree and blackberry and Himalayan honeysuckle. When she looked closer, she found a mass of living things. There is a great variety of native birds, some using weeds as habitat. There are insects galore: “The swamp is a rich ground for all sorts of life,” she says. “I’m also interested in this area because ecological restoration is going to be undertaken as part of the Planetary Health project. It’s going to be interesting to observe this swamp over a longer period and see what happens as the weeds are replaced with natives.”

Dragonfly – Fiery Skimmer (Fiona Vaughan)

Blue Mountains City Council’s Bushcare program will play an important role in this, with their Woody Weed Wanderers and Swampcare coordinators and volunteers already looking after different aspects of the swamp. This involves weed control, fauna monitoring, plant identification, seed collection and other activities. In 2002, Bushcare had its 30-year anniversary. It’s a significant point in time on Blue Mountains City Council’s sustainability journey.

Freedom says, “Our Blue Mountains City Council is amazing in how it supports Bushcare. I think there are about 60 Bushcare programs run by the Council and a significant proportion of those are Swampcare programs. It’s quite unusual I think to have so many people volunteering in a community. People just seem to love this place and want to take care of it.”

Justin Morrissey and Freedom Wilson

Justin Morrissey

Justin Morrissey, curator of Recovery: The Exhibition, is down at the golf course. Freedom asked him to come on board with the Swamp Diaries so he’s looking after the website, and finding opportunities to expand the group’s activities. They are holding an exhibition during Science Week in Sydney this year. Justin is a volunteer like everyone else. He tells me that everyone does it for love. They all see the value of telling stories about swamps to enrich them as a community group. But it also provides an opportunity to express and communicate with others about swamps, to share their passion for the place.

Justin is a producer, curator and writer working primarily in visual arts and performance. In 2020 he received a Churchill Fellowship to examine how social innovation in creative programming mobilises civic engagement. He was interested to learn what art can do to bring people together.

He tells me that many of the artists volunteer with Blue Mountains City Council’s Bushcare: “There are numerous ways in which people can contribute to caring for the land,” he says. “We’re also out there planting and repatriating and weeding and getting our hands dirty, just not every minute of every day. We have to make sure we don’t feel burned out and completely exhausted by eco-activism. We’ve all survived floods, fires and viruses. Finding ways to look after ourselves is incredibly important.”

Justin has a deeply personal connection to this work as a Blue Mountains local who experienced the disasters of recent years:

“Making art is a way to seek solace in nature, even while it’s falling apart around us. I think that that’s something we all felt deeply about during Recovery. This notion that we were part of the solution, us as individuals. We felt like we had the power to overcome a lot of the grief that we were all experiencing after the fires.”

Justin Morrissey

One of the things the group discovered when they started researching swamps was an international movement of artists in swamps. Justin recently visited the Scottish peatlands on the Isle of Lewis, hoping to connect swamp artists there with swamp artists here. He is proposing an artists’ residency exchange, where Australian Aboriginal artists travel to Scotland and Scottish artists, who are also mapping their peatlands and swamps, come to the Blue Mountains. Justin says that the vision that has come together around upland swamps in the Blue Mountains is about language, Country, and our whole planet.

Emma Magenta

Emma Magenta with a copy of Annie Proulx’s Fen, Bog & Swamp

I catch up with Emma in Blackheath. I see her coming down the arcade, book in hand, dirt on knees of work trousers. The book is Annie Proulx’s inspiring Fen, Bog & Swamp. It’s a history of peatland destruction and its role in the climate crisis.

Emma was the MC of SwampFest at the RSL last year. She says Professor Ian Wright gave an amazing talk. She contributed artwork for the auction, and tells me of her surprise that the giant paper mâché Swamp God she’d made at the last minute sold.

Emma’s interest in the Swamp Diaries traces back to her childhood. She remembers seeing a crack in the ground in her parents’ backyard. She was small compared to the crack and recalls thinking: “Does this mean that the earth can break apart?” She was similarly struck by a dripping tap: “I felt this instinct to turn the tap off. Something inside me said that one day water was going to be scarce.” I can almost see that child realising that the earth is not an impervious constant mass, but dynamic and changing, something humans can have an impact on.

With La Niña in full force, we haven’t had an absence of water in recent years, but Emma has seen what happens with water and how it affects the Blue Mountains. Since 2013, she has walked every day along a road in Medlow Bath that adjoins an urban swamp. “It looks like a dead end, but there’s forest in there and the swamp, and lower down a water catchment area.”

Medlow Bath Swamp (Emma Magenta)

She says one of the curious things is that there are a number of massive pines. During Covid, a nearby property cut down lots of large pines and built several new structures. Emma observed that this has changed how the water behaves. Torrents of water rush more frequently into the pipes that feed into the swamp. This could create channels that expose the peat. It could bring more nutrients that stimulate the growth of weeds. She has been photo-documenting her walks for years and says the number of weeds present on the road adjacent to the swamp has significantly increased.

This is likely caused by a combination of things. More concrete decreases absorption of water and therefore increases runoff. Trees are extraordinary water pumps. They draw in water through their roots and transpire through their leaves. Large trees can move hundreds, even thousands of litres per day. With fewer trees, there is less water moving back into the atmosphere, so more water is running on the ground.

Emma thinks that COVID may have exacerbated the runoff issue because people did so many renovations. This meant more concrete and less vegetation to absorb moisture. “It’s a systems challenge,” she says. “People have the legal right to do it, but the effect that everyone doing it has, is something to be addressed at an urban development level.”

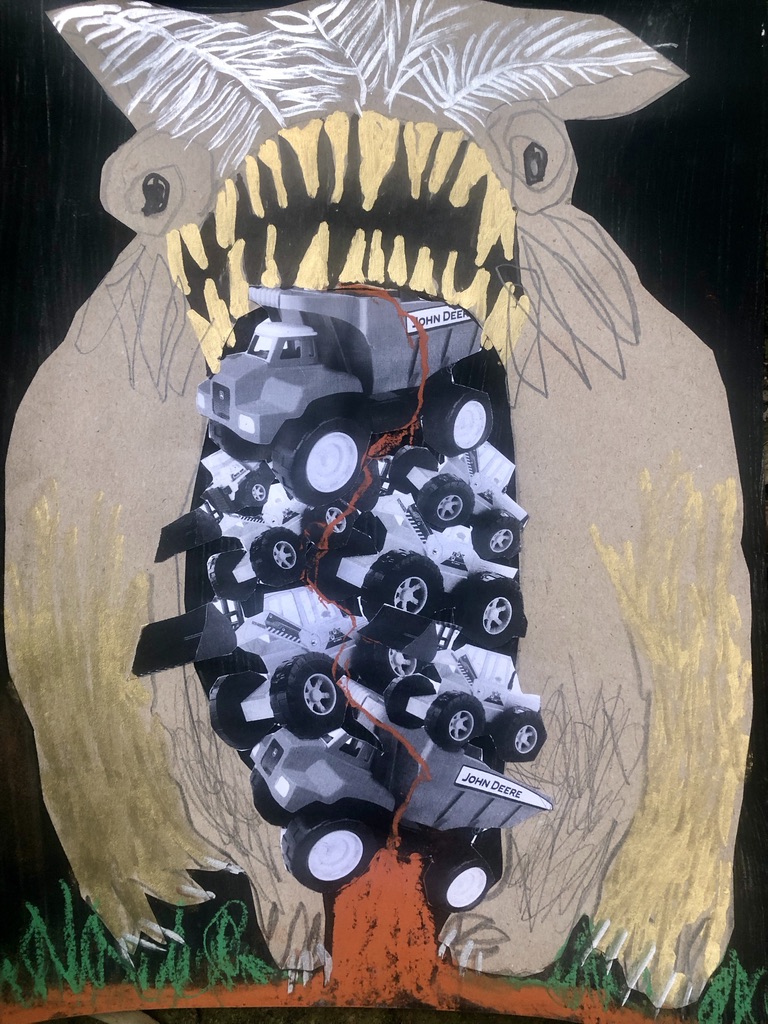

I’m interested in how Emma’s artwork will be shaped by these observations. She draws and takes photographs, writes and makes sculptures, mostly from found objects. One of her practices is to draw with her non-dominant hand. She says the results are childlike, but it’s a way of making herself conscious of what’s she doing and how she’s doing it. “Do you know the artist Jeff Koons and his metal balloon dogs?” she asks. I remember seeing them, some ornament-sized and some imposing public sculptures. “I’ve got this idea,” she says. “I want to build a giant bunyip-like creature with its stomach filled with Tonka trucks!”

Emma Magenta’s drawing to create the giant Bunyip (Emma Magenta)

To me, this artwork could be interpreted as a wrestling match between human and non-human, but Emma talks about the importance of not presenting dualities. She gives me an example: “It’s like focusing on urban development verses swamp protection. This duality – black and white – can limit our ability to look for broader solutions. I think swamps are like art in the sense they provide a place for us to reflect and explore new ways of seeing.” Emma looks across the table at me. “It’s important, right? We all need to find a way forward together.”

“It is easy to think of the vast wetland losses as a tragedy and to believe with hopeless conviction that the past cannot be retrieved – tragic and part of our climate crisis anguish. But as we see how valuable wetlands can soften the shocks of change, and how eagerly nature responds to concerned care, the public is beginning to regard the natural world in a different way. The ‘rights of nature’ is a legal concept that is gaining international standing.”

Annie Proulx: Fen, Bog & Swamp (2022)

In 2021, Blue Mountains City Council became the first Council, and government, in Australia to adopt the Rights of Nature.

The Swamp Diaries spans 2023. Information and updates can be found on the Eco-Art Space website, and you can follow the artists on Instagram @the_swamp_residencies.

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.