A drone’s view: Hamish Dunlop, Richard Delaney and Trent Forge (Richard Delaney)

Story and photos by Hamish Dunlop

Trent Forge from NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service and drone pilot Richard Delaney search for the critically endangered Isopogon fletcheri. Using drone technology, the cliffs and hanging swamps of Blue Mountains National Park can be surveyed in a way previously impossible. Read below about the discovery of a new population of this rare Blue Mountains plant.

Key Points:

- The Greater Blue Mountains Area is home to the incredibly rare Fletcher’s Drumsticks.

- Drone technology has revolutionised the conservation of this critically endangered species.

- Learning about biodiversity and conservation efforts is a great way to connect with the extraordinary place we live in.

“He’s got a nose for it!”, Richard exclaims, as Trent Forge from the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service lightly touches the view screen. “A bit down,” Trent says, “and slightly left.” The camera on the drone Richard is piloting switches from 1x to 3x optical zoom. Richard can see it now too, but I’m still mystified by the mass of green on the screen. When the drone camera changes to 7x optical zoom, I can finally see what Trent has spotted: the critically endangered plant, Isopogon fletcheri.

A drone’s view with Isopogon fletcheri at 7x optical zoom in details to the right (Richard Delaney)

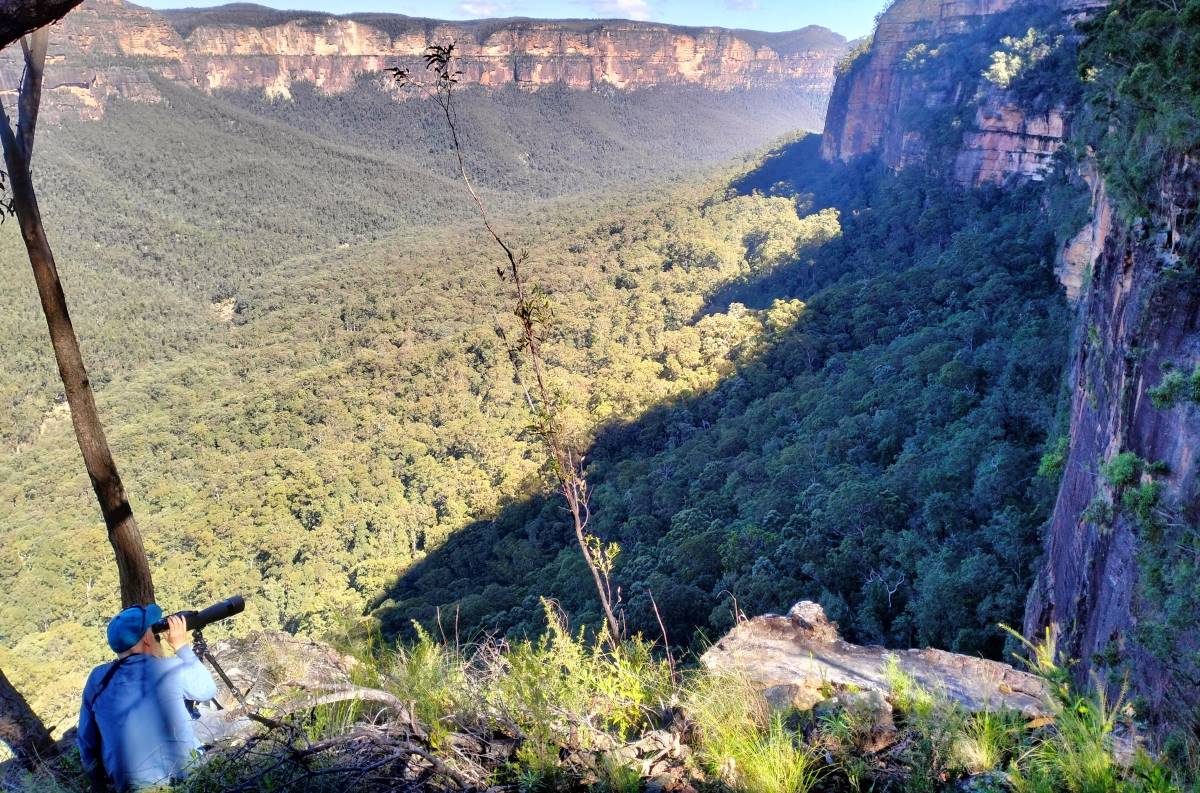

Looking across from just above Bridal Veil Falls in Blackheath, the drone is a barely visible dot against the vast escarpment wall below Govetts Leap. The wall is covered with hanging swamp fed by water seeping out of the rock. The cliff rises majestically out of the Grose Valley and is home to the largest population of Fletcher’s drumsticks (Isopogon fletcheri) in the world.

Saving our Species

Fletcher’s drumsticks only exists in the Blue Mountains. They’re a relic of the Gondwana supercontinent, reaching back into deep time, millions of years ago. There are approximately 300 plants in this location, the largest population of the approximately 1000 plants known to exist.

This rarity makes searching for new populations an important part of the conservation project. This is complicated however: Isopogon fletcheri predominantly grows on wet cliffs that are inaccessible on foot.

Trent and Richard with the cliff below Govetts Leap in the background. (Hamish Dunlop)

Trent is a Threatened Species Officer with the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service. He says drone technology is providing a tool to undertake conservation biology in a way never before possible. “More than 90% of the known population for this species occurs on cliffs,” he says. “Using drones make surveying this cliff-hanging species efficient, and in some cases, it would be practically impossible to do otherwise.”

On the lookout

Today Trent and Richard have come to explore a cliff section on the south side of the Grose Valley. Richard is a certified drone pilot and works with Trent to identify and record new populations. He tells me he’s ‘just the muscle’, but confesses he’s been involved with the protection of endangered species in the Blue Mountains – such as the Dwarf Mountain Pine – for a large part of his life. (See Linda Moon’s story here and watch Will Goodwin’s video here to find out about this endangered species.)

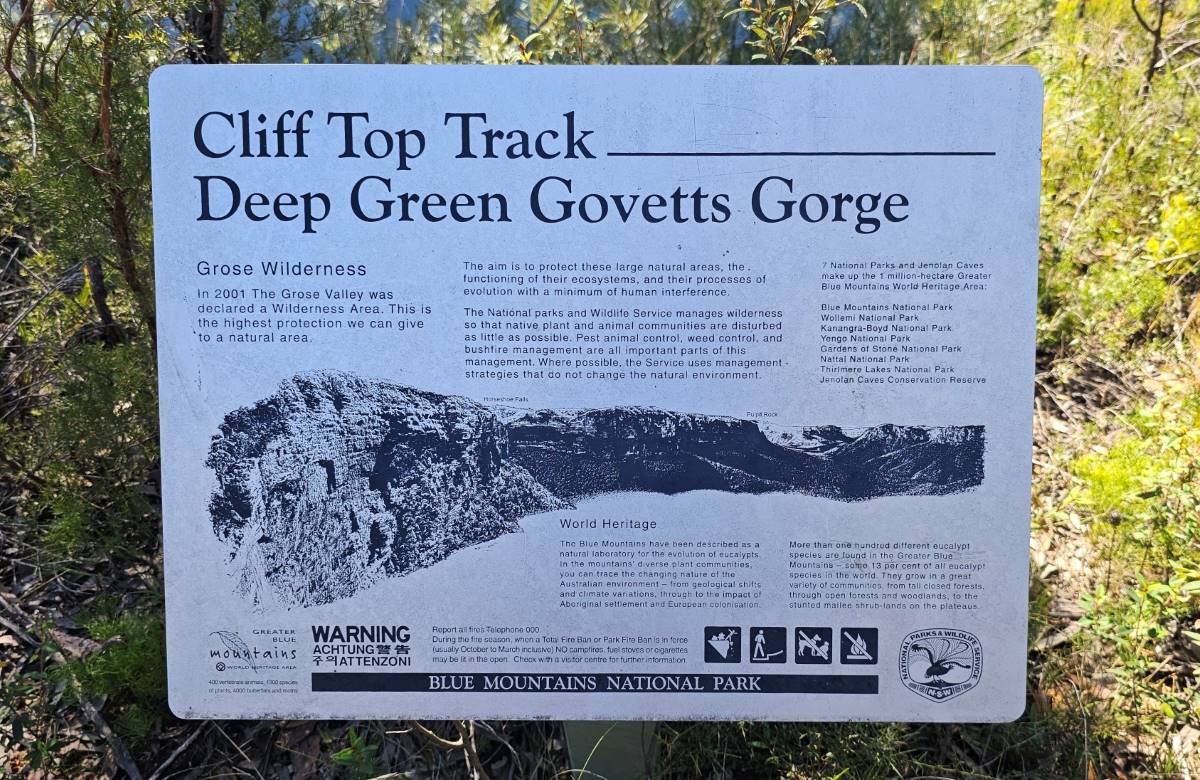

Signage along the Evans Lookout to Govetts Leap track. (Hamish Dunlop)

We’ve come to a particular spot along the walk between Evans Lookout and Govetts Leap. We’re chasing a record of a small population discovered by Department staff member and local, Philip Gleeson, with a spotting scope a year ago. It’s a scramble to access the area and we don’t find anything on the clifftop. Trent and Richard have been looking at satellite imagery though and have identified areas below with promising habitat

“It has two predominant ecological niches,” Trent says. “They are either southeast or northeast facing. The northern side populations can be less saturated because they are less exposed to sun – the plants can grow in wet cracks. The southern side populations catch more sun, so are usually restricted to hanging swamps.”

“There are two main areas where Fletcher’s drumsticks are found: in the Grose Valley ranging as far east as Explorers Wall below Mount Caley, and in the Kedumba Valley. It needs to be wet and not too exposed,” Trent explains. “If there are grass trees growing for example, it’s probably too dry.”

Philip with spotter scope (Photo: Liam Ramage)

Taking flight

Richard holds the drone aloft and its blades whirr into action. He carefully navigates through the treetops giving the drone’s camera an uninterrupted view of the cliffs. Trent directs Richard to various locations.

Within 5 minutes, an individual plant has been found. That quickly turns into four. It’s exciting to be part of this discovery. Richard goes back later in the day when the light is more favourable and tallies 41 individuals. It’s an incredible find.

Richard launching the drone. (Hamish Dunlop)

“It’s not a natural ability, that’s for sure,” Trent says, talking about how he intuits where plants might grow. “I’ve been doing this for four years. You get to know the plants’ niches. You also get skilled at picking up shapes and shades created as the drone changes its aspect. Sometimes there are telling dead branches that droop down. The leaf colour is distinctive too, and the leaf shape is characteristically Isopogonish.”

The endangered species program

Finding new populations is just one part of the Isopogon fletcheri conservation project. The Research Centre for Ecosystem Resilience at the Australian Institute of Botanical Science, Royal Botanic Gardens completed genomic sequencing to establish the species’ genetic diversity.

A plan is now underway to create an ex situ population. “This will involve propagating and establishing plants, and then maintaining these in a secure location, for example in a botanic garden” Trent says.

Trent identifying possible Isopogon fletcheri locations using the drone’s camera view. (Hamish Dunlop)

Education is another important part of the conservation effort. The challenge faced by species such as Isopogon fletcheri is correlated with human-affected climate change. “In the Blue Mountains, we’re going to see more periods of drought,” Trent explains.

“Drier conditions will disproportionately affect species that thrive in water-soaked habitats. We also lost between 5% and 15% of plants in the 2019/20 fires. This increase in disasters such as bushfire is directly related to climate change.”

There are a huge number of species that are already endangered and becoming threatened in New South Wales, Trent continues. “We are at risk of losing 1000 species and ecological communities. “The Saving our Species program in NSW is focused on these.” Trent believes the increase in endangered species and extinctions should be like a canary in a mine. “It should motivate us to reduce our contributions to climate change, such as burning fossil fuels.”

A closeup of Isopogon fletcheri (Photo: Philip Gleeson). The species is classed as Vulnerable at the state and federal level and as Critically Endangered on the International Union for Conservation of Nature database.

Mud on your shoes

One of the activities NPWS undertakes to protect Isopogon fletcheri is rerouting tracks to avoid specific populations. “We know this species is susceptible to Phytophthora cinnamomi, a water-borne mould,” Trent explains.

“Phytophthora has been detected in several I. fletcheri populations that have been accessed by the public, with some individual plants showing early signs of disease. Unfortunately, it can be carried into sensitive areas on people’s shoes and boots. We’re particularly concerned about off-track walkers and rock climbers in the Northern Grose Valley.”

There is an urgent need to stop the spread of Phytophthora cinnamomi in the Blue Mountains. (Photo: Miya Tsudome)

Richard, who pilots the drone, ran an environmental management consultancy for ten years and has a Master’s degree in Environmental Management. He’s a local legend in the climbing community as well. He says, if possible, footwear should be cleaned of mud. “If you want to be extra careful, use methylated spirits or 70% isopropyl alcohol to disinfect your shoes. This reduces the chance that you’re tracking diseases between locations.”

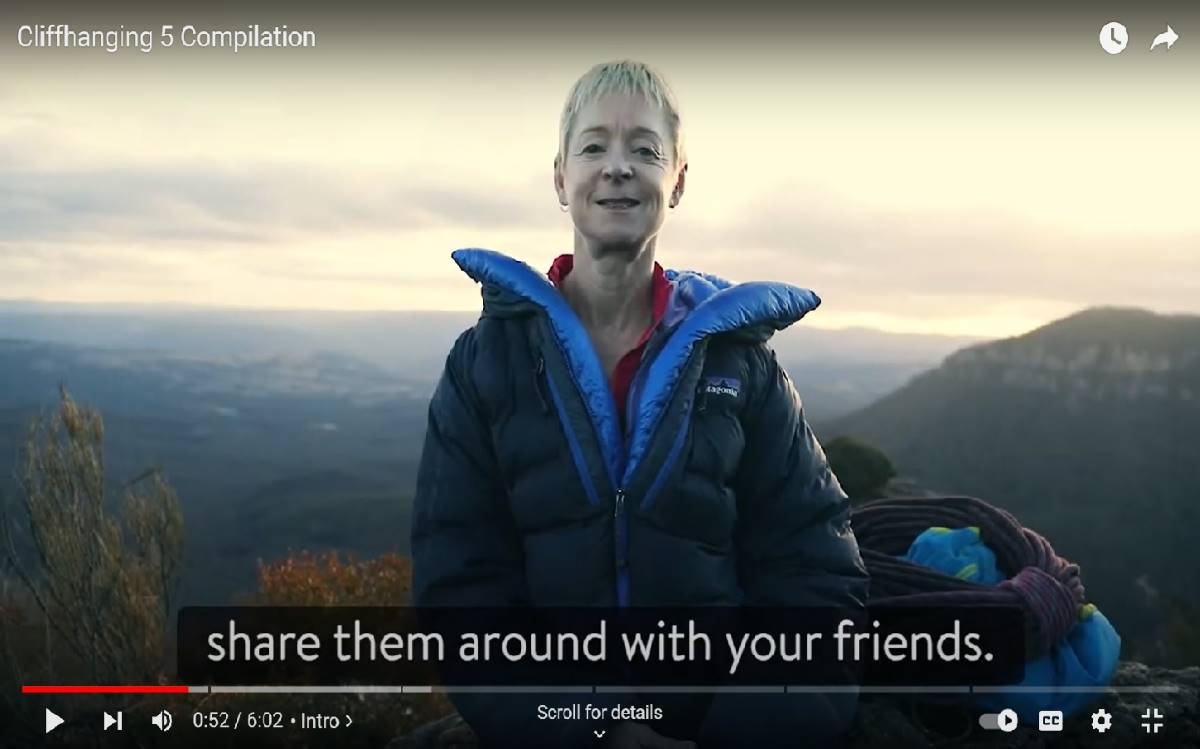

He’s realistic about how much people are willing to do, but remains motivated in the work he does. “Raising awareness is a key outcome of these efforts. We are so privileged to live in this incredible place. It’s worth knowing that a plant that gets damaged as you’re climbing, or making new tracks, might be one of only a few in existence. There’s a great resource called the Cliffhanging 5. It describes five amazing, threatened plants to look out for around the rugged cliffs of the Blue Mountains.”

Blue Mountains resident and climber Monique Forrestier talking about the Cliffhanging 5. Watch the video here >

The intrinsic value of life

Richard is passionate about doing conservation field work. “Every time I go looking for them, they teach me something,” he considers. “I learn about their habits and habitat. When they flower and how they can reshoot after bushfire for example. But I don’t have to see them to appreciate their intrinsic value. It’s not just about the value of plants to humans. They have a right to exist, regardless of our level of appreciation.”

Trent is also deeply connected with the natural world. He knew from the age of ten that he wanted to be a conservation biologist. “I grew up on a farm and was obsessed with animals,” he says. “When I was given the Readers Digest Complete Book of Australian Birds, I identified all the birds on the farm. Caring for endangered plants is different. They often don’t have the profile of other species likes quolls or koalas. That means there’s a real opportunity to better understand their distribution and numbers.”

Like Richard, he sees conservation work as critical in its own right, but believes it’s an opportunity to understand how human activity is impacting our world at the local level. “When you look at what is happening to species, you start to get an idea about how everything in nature is connected,” Trent says. “I think seeing this web of interconnectedness can help us think differently about the challenges we and the planet face.”

Takeaways:

- We share the Greater Blue Mountains Area with some of the rarest plants in the world.

- Knowing about these plants and our environment can connect us to the challenges we and the planet are facing.

- When out and about in the bush, cleaning footwear can reduce the spread of pathogens such as Phytophthora cinnamomic.

Share this article:

This story has been produced as part of a Bioregional Collaboration for Planetary Health and is supported by the Disaster Risk Reduction Fund (DRRF). The DRRF is jointly funded by the Australian and New South Wales governments.

More from around the region

@ bluemountainsplanetaryhealth . Apr 25

Over 80 people gathered in Peace Park Katoomba today to reflect on all victims of war: those who died in battle; those who were maimed physically and/or psychologically; the suffering of loved ones and relatives on the homefront; and those who opposed conscription and war. It was an opportunity to reflect on the causes of war and call for a future of peace and reconciliation. @bm_peace_collective

#peace #anzacday #peacenetwork #planetaryhealth #katoomba #bluemountains

@ bluemountainsplanetaryhealth . Apr 23

‘The resistance’ to the destructive forces at play in our world is alive, well and spreading infectiously in the welcoming and inclusive zine community. Zines are small, handmade independent `magazines` that are not-for-profit and made for love. Read about the recent inspiring Blue Mountains Zine Fair in our Katoomba Area Local News here: https://www.katoombalocalnews.com/blue-mountains-zine-fair/ (link in profile)

and go along to the Mtns Zine Club`s monthly meet-up for making, swapping and sharing zines this Sunday 27 April at the Blue Mountains Cultural Centre from 1.30 to 3.30pm (usually on third Sunday of each month)

@mtnszineclub

#zines #independentpublishing #resistance #planetaryhealth #club #bluemountains #katoomba #artmaking #creative

@ bluemountainsplanetaryhealth . Apr 21

Do you have food growing in your garden over winter? At our next Skill Share on Saturday 3 May you can find out which edible foods grow well over winter in a cold climate, and get hands-on experience building and planting out a no-dig garden bed with a winter crop at the Planetary Health Centre.

Through this process you will be given an introduction to permaculture and learn more about seed saving, seed germination, composting and cold climate gardening strategies.

Seeds and seedlings will be shared to help you get started at home! Places are limited so bookings essential here:

http://bit.ly/4jqRerw (link in profile)

#coldclimategardening #wintergardens #ediblegardens #bluemountains #katoomba #planetaryhealth #permaculture #skillshare

@ bluemountainsplanetaryhealth . Apr 19

At the Blue Mountains Interfaith Gathering on the 30 March, 97-year old Sister Jacinta Shailer from the Sisters of the Good Samaritan urged us to respond to the increasing challenges facing us by `joining heroic communities’. Read more about what she said and all the other inspiring contributions on the day in our Katoomba Area Local News here:

https://www.katoombalocalnews.com/create-heroic-communities/ (link in profile)

#interfaith #heroiccommunities #bahai #brahamkumaris #quakers #unitingchurch #catholic #bluemountains #planetaryhealth #katoomba @planetaryhealthalliance

@ bluemountainsplanetaryhealth . Apr 17

@ bluemountainsplanetaryhealth . Apr 17

Our Planetary Health newsletter is now out! Read about the Trainee Administration Position available with the Planetary Health Centre, our upcoming workshops, and the Heroic Communities of the Blue Mountains who are finding housing for older women; creating inclusive and creative alternative media with zines; sharing their faith in the value of compassion, love, kindness, gratitude and joy; and sharing skills for improving physical and mental health and restoring habitat for wildlife, reducing textile waste and growing seeds and edible gardens.

Follow the link here:

https://bit.ly/42l8W9O (link in profile)

#jobs #planetaryhealth #housing #housingforolderwomen #skillshare #bushcare #ediblegardens #heroiccommunities #zines #seedsaving #interfaith

@ bluemountainsplanetaryhealth . Apr 9

@ bluemountainsplanetaryhealth . Apr 9

@ bluemountainsplanetaryhealth . Apr 6

It was gloriously sunny and we had a fabulous day of sharing at the Planetary Health Centre yesterday, from T`ai-chi to workshops on the Frogs of the Blue Mountains, Fashion Upcycling and How to Build a Survival Garden in the Blue Mountains. We finished with a Bushcare session in which we enjoyed the beautiful bushland on the site and removed invasive weeds to expand the habitat for wildlife around our swamp. We were joined by frogs in our pond and the little echidna who returned for a swim! Thank you to everyone who shared so generously. We tasted Yacon and shared rhizomes, Purple Congo Potatoes, Oca, Turmeric, and seeds for Salsify, Egyptian Spinach, Red Mustard, Echinacea, Parsley, Chard, Radish, and Red Noodle Beans. Our next Skillshare Saturday will be on the first Saturday of May. If you`d like to be notified of all our workshops, and the meetings of our Seed Saving and Gardening Groups, subscribe to receive the fortnightly Planetary Health newsletter at any of our Local News sites like www.katoombalocalnews.com (links in profile) #skillshare #planetaryhealth #taichi #qigong #frogs #bluemountains #katoomba #fashionupcycling #upcyclingfashion #survivalgardens #seedsaving #loofah #community

@ bluemountainsplanetaryhealth . Apr 3

Our Skillshare Saturdays are on the 1st Saturday of every month and we`re looking forward to a beautiful sunny day tomorrow for our first Morning T`ai-chi & Qigong. Fashion Upcycling is booked out this month, but we still have a few places for Frogs of the Blue Mountains, Building a Survival Garden and Planetary Health Bushcare. Bookings via Eventbrite (links in profile). For more information ph. 0407 437 553

#skillshare #planetaryhealth #sunnyday #katoomba #bluemountains #taichi #qigong #frogs #seedsaving #survivalgardens #bushcare

@ bluemountainsplanetaryhealth . Apr 2

Imagine, if just once a month, everyone gave a few hours back to nature to repair the damage we`ve done. We would so quickly restore the habitat of so many species struggling to survive and provide the habitat for many more to flourish. Once a month, for three hours, our Planetary Health Bushcare group does just that. We`re repairing the damage of human impact and being immediately rewarded by our time in nature and the great company of the other members of our Bushcare Group. We`ll be meeting again this Saturday 5 April at 1.30pm and all are welcome to join us and learn more. Contact Karen Hising at khising@bmcc.nsw.gov.au or call the Bushcare Office on 4780 5623 if you`d like to give it a try.

For more information about the Planetary Health Centre and how you can get involved contact the Planetary Health office on 0407 437 553

#bushcare #biodiversity #wildlife #habitat #regeneration #planetaryhealth #community #allinthistogether #bushcare #katoomba #bluemountains

@ bluemountainsplanetaryhealth . Apr 2