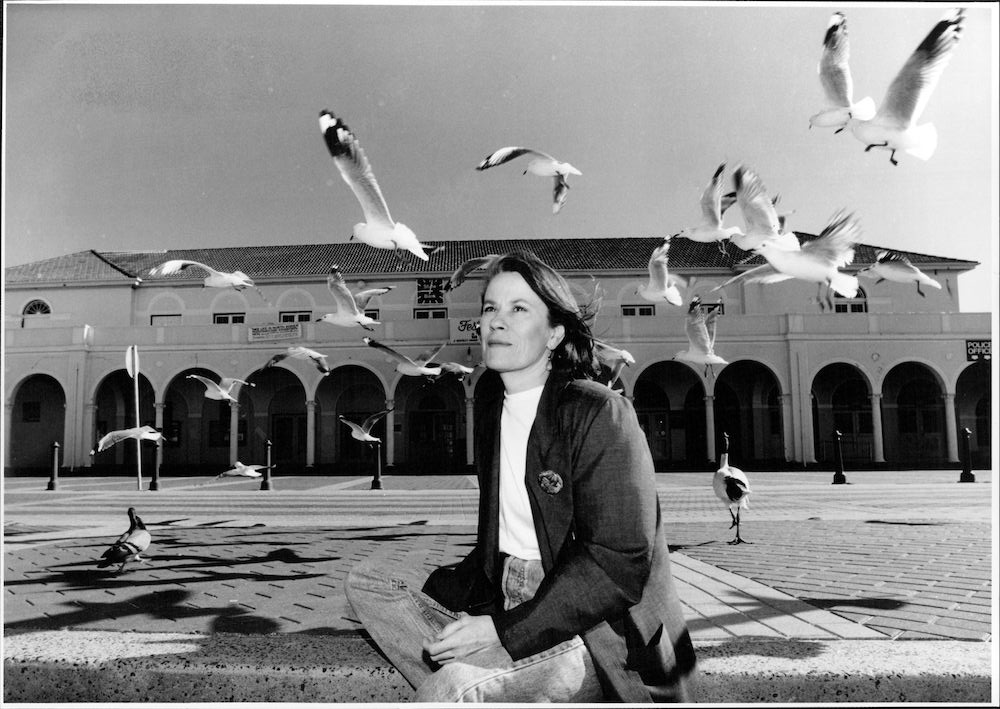

September 3, 1993. (Photo by Robert Pearce/Fairfax Media).

Annabel Pettit shares her inspiring conversation with Barbara Armitage, former Mayor of Waverley, about her passionate dedication to family, community and creativity.

To set the scene, it’s 1988, and you’re not in the Blue Mountains right now, but rather walking down Roscoe Street in Bondi, headed to the beach. Thatcherism, neoliberalism and HIV/AIDS are still on the rise, but so is INXS – it’s not all grim. Barbara Armitage has just been elected mayor of Waverley, and you unknowingly walk past a former brothel that she has converted into a homeless shelter. In the coming ten years, she will bring corrupt developers before the ICAC, save the Bondi Pavilion from privatisation and rebuild the local community services from dust. You turn up the walkman and pick up the pace.

It’s 2021 again in Blackheath, we are sitting in Barbara’s living room and I have just asked her, of these achievements, which she is the proudest of. Her response:

“Nothing really. I mean to me it’s just what people who are elected officials should be doing anyway – responding to community needs and not falling for small vocal groups that have got the money.”

I found this impersonal response to a highly personal question both endearing and revealing of Barbara in the very best way. This is not self-deprecation or false modesty, but rather the response of somebody for whom community care is simply hard wired into their default setting; a basic fact of their being and purpose. Despite this wonderfully lucid response, even the briefest overview of Barbara’s life would suggest otherwise. One conversation leaves you with a strong rebuttal case, and enough evidence to argue that there is in fact a great deal of which Barbara could be proud. Before her life as Mayor, Barbara was working full time as an associate to a justice in the Supreme Court and as the single mother of three children.

Her own mother was an “intelligent woman who was not able to use her intelligence”. Barbara seemed to be using her’s enough for two, since she was simultaneously researching properties that had been marked for a change in their status zoning, and quickly found that they all belonged to the associates of a newly employed town planner. This “rezoning” would have translated to the Bondi beachfront becoming a horizon of high rises.

“I knew there was something going on, but it took me a long time to do the research and get all this stuff together … there were thirteen fires in the Bondi Junction area of buildings that they obviously wanted to redevelop, so they were very corrupt”, says Barbara.

Over the course of ten years, she researched, meticulously gathering evidence that developers and the town planner were accepting bribes. It was enough to convict them, and thus make herself the enemy of an entire network of Sydney’s most wealthy and powerful. This ICAC file is now the unusual badge of honour that lives in Barbara’s downstairs cupboard in Blackheath – a spot where one would more typically find an ironing board.

Her transition into local government followed the realisation that fake eviction notices were being sent to members of her community, many of whom were vulnerable and unable to interpret them as fraudulent. Barbara explained the situation in plain english, dropping letters into every mailbox to reassure those affected that they could sit tight in their homes.

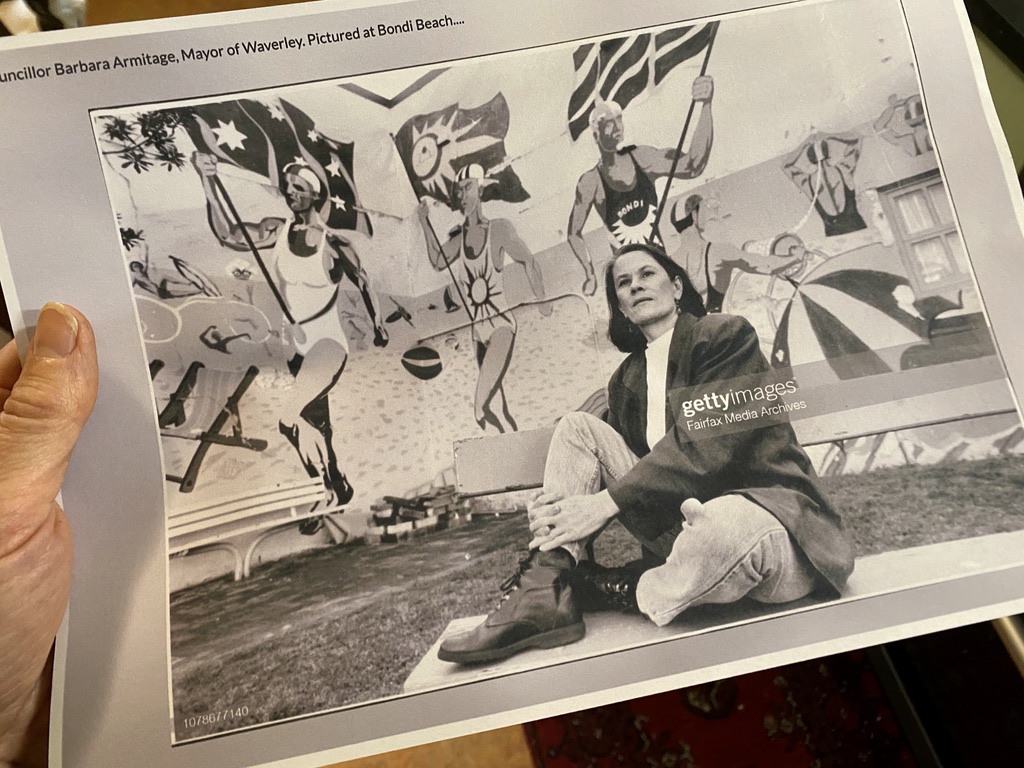

Photo (detail) by Anne Zahalka

In 1988, Barbara won the local election in Waverley, overturning approval for the ‘Bondi Babylon’ project that would have lead to the beachfront’s high rise development (1) . This was an era of ruthless privatisation, characterised by Margaret Thatcher’s attacks on the NHS, and Australia’s nationalised industries or public housing were in no way excluded from these neoliberal policies.

Barbara responded to the gaping hole in community services by setting up centres for intellectually disabled locals and childcare, women’s refuges and homeless shelters, as well as ensuring that the Bondi Pavilion remained a council-owned space open for free public use. This was a far cry from the mayoral trend of approving a change in zoning status under the influence of a sweet tip on the side.

Barbara was the kind of mayor who was more likely to receive a brick through her car window than a wad of illicit cash. Although having your window smashed by Sydney’s most wealthy and powerful is a great mark of pride on one hand, it is also an indication of the real price that community activists often have to pay when standing up to the lucrative, well-armed world of developers. Ten years before Barbara first began investigating their private dealings, the Sydney newspaper owner Juanita Nielsen was kidnapped outside of a Kings Cross club which was owned by the notorious hotelier Abe Saffron (2). (In an Australian remake of The Godfather, Saffron, the “Boss of the Cross”, would be the Don.) Barbara recalls how Saffron regularly came in and out of the Council building to visit town planners, and had lent a large sum of money to a certain developer named Frank Theeman (3).

Theeman was responsible for destroying some of the historic properties in Kings Cross which Nielsen had taken a leading role in defending alongside the mighty BLF – the Builders Labourers Federation, which led the wave of 1970s union militancy. Their green bans are responsible for most remaining sites of beauty in Sydney’s centre, and were costing Theeman $140,000 a week by early 1974. (4) However, Juanita Nielsen’s vocal activism against corruption, forced evictions and development, culminated in her disappearance outside of Saffron’s Carousel Club, on the 4th of July 1975, and she has since never been found.

Thus in the late 80s, Barbara was knowingly and publicly acting in Nielsen’s shadow – under no illusions in regards to the stakes involved, or to the expanse of Sydney’s underworld web. And although she thankfully never went missing in the dead of the night, the message from Barbara’s enemies was always conveyed, consistently, more covertly, and at times absurdly. For instance, she recollects how her dog would end up at the pound, “the moment he stuck his nose out the door”, or how her youngest son Stuart received a traffic infringement notice for ‘driving an unsafe vehicle’ (this great threat to the streets of Bondi being his skateboard).

The town planner who Barbara was investigating was also in charge of the local surf club, so Stuart would be caught in the crossfire, harassed by lifeguards in secondhand acts of revenge against Barbara. Juanita and Barbara’s experiences are an insight into what happens when an individual puts themselves on the line and in the way of the endless drive for profit.

It was in turns amusing and disturbing to hear just how high a price one could pay for simply claiming that your community’s needs should be put first.

However if you have made it onto the property developer’s most-wanted list and the local police have a bounty on your dog, I tend to think you’re doing something right.

There is a brilliant photo you can find of Barbara through a quick google search – taken as mayor sitting before a Bondi mural, looking contemporary, smart-casual and impossibly cool.

We show her a printed out version of it, and her immediate response is this: ‘they buggered up that mural, it really made me angry’. To have a mayor for whom every mural is of weighty significance is a rare thing, and the fight which Barbara waged is an ongoing one.

Last year, Waverley Council received a proposal to rope off a section of Bondi Beach and charge $80 entry to the so-called ‘Amalfi Beach Club’, which is explicitly aimed at “high-net worth individuals” (5), and has received nearly 1000 signatures in its support. There’d be no question as to what Barbara would have made of this proposal.

Legend has it that – as in A Tale of Two Cities, in which the female revolutionaries would bring their knitting down to the guillotines for entertainment, Barbara would bring her knitting to council meetings, systematically rejecting each developer’s plan, stitch by simple stitch. Looking at the needles on her craft table in Blackheath, I like to imagine they were waved in the face of some

red-faced, briefcased developer back in the 80s.

The unofficial centrepiece of Barbara’s own home in Blackheath today is her craft table. Beads and crochet hooks overflow, acting as small scale conduits that help to feed her insatiable appetite for creative solutions. Children’s artwork on the walls oversee the whole process, beside pencil markings which hold the proof of grandchildren’s growth spurts – like man-made tree rings. Visible reminders of where we come from. It wasn’t until one of her later growth spurts that Barbara herself was even admitted a full education. Being partially deaf in the 1940s meant being dismissed as “slow” until the age of 12. Her whole subsequent life is the sweetest vindication of just how far-off this early assessment of her supposed ability really was. There is simply nothing “slow” about it.

Sitting at this craft table, surrounded by clear plastic tubs of beads, Barbara remembers staying back after school to help build sets with her art teacher, and she still feels the thrill of coming home to find that her mother had bought her a copy of ‘Art Through the Ages’.

“You have to have some creativity in everything you do”, she tells me.

“When I go to bed at night I dream of how to solve problems and it can be anything from making jewellery to cutting up a piece of wood, or solving a personal problem somebody’s got, and you get lost in, just completely lost, in what you’re doing and the whole world seems good.”

This lateral instinct which comes with creativity is the same one which informed her work as a mediator. This part of Barbara’s career began after her work as an associate in the Supreme Court, where complex cases inevitably need to culminate in one winner and one loser. In response to this structure, Barbara wanted to offer an accessible mediation service to create environments wherein anybody could have the opportunity to “communicate in a non-combative way”.

“Look at how Aboriginal people manage disputes, every culture has its way”, she says.

One of Barbara’s earliest and most treasured memories goes a little like this: she is five years old, and her Dad’s caravan is parked on the side of the Murrumbidgee river, which has flooded. The family is held up, briefly stranded en route to Wagga Wagga. There’s an Indigenous family further down the river. Her sister befriends one of the girls, who is wearing a red and white spotted polka dot dress, and Barbara watches the two girls play while her parents get on top of the situation. All that their game involves is picking up leaves together and putting them in a paper bag. Surrounded by the uncertainty of adults scuffling around broken caravans and flooding rivers, these two girls exchange a moment that is playful and peaceful. There is no winner or loser, not even any words spoken, and yet something is still communicated.

This is the same spirit which Barbara has carried from the time she was a young girl fascinated by art, to a grown woman and professional mediator – the belief that through creativity, some kind of relative neutrality, objectivity or understanding can be reached.

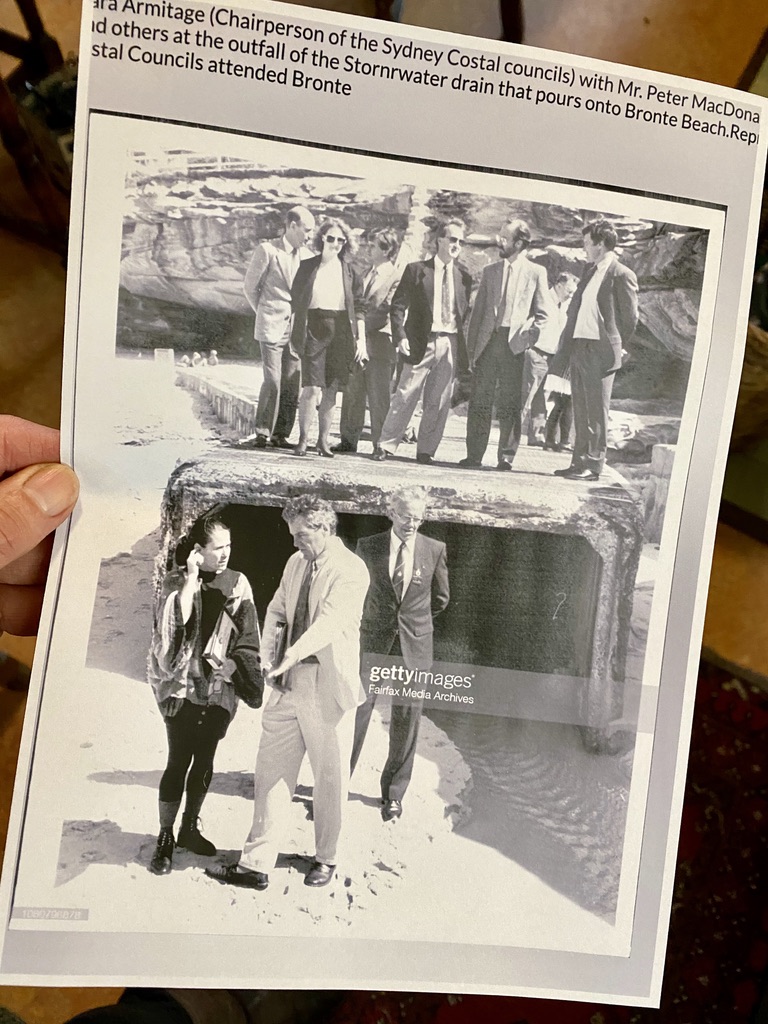

This personal zeal for creativity surfaced at different points in Barbara’s professional life, such as overseeing the inaugural Sculpture by the Sea exhibition in 1997. This is now an annual staple of Sydney, but Barbara was its champion long before public arts events such as Vivid were in vogue, and when the founding director had a meagre $100 in the project’s bank account. This was also in the wake of a decade’s-worth of environmental campaigning around the health of Sydney’s water, which formally began under Barbara’s leadership in 1989 with the formation of the Sydney Coastal Councils Group.

This was a nonpartisan group which united councillors with swimmers, surfers and activists who wanted to devise a strategy to combat the dumping of the city’s waterways and ensure the conservation of our harbours. Their movement spread the stretch of the coastline from Curl Curl to Malabar, grew throughout the 80s and culminated in 1989 with “Australia’s Woodstock against pollution” – the ‘Turn Back the Tide’ Rock concert at Bondi Beach, where 200,000 people joined the likes of INXS, Midnight Oil, Icehouse and the Divinyls to demand cleaner ocean water. After meeting with the Environment Minister, John Farnham addressed the crowd: “they told us that the sewage they pumped into the sea was diluted one part in ten. They expect us to swim in that ?”

Among ICAC files from developer’s trials, other unlikely badges of honour which Barbara harbours in her downstairs cupboard are photos of her and her children backstage at Bondi Beach with the members of Dragon. As I said – impossibly cool. When listening back to the recording of our conversation, two things stood out to me:

1) We laughed so much. Barbara is wry, warm and always a step ahead of us. She exudes my favourite kind of warmth – no time for over-sentimentality, or patting yourself on the back for what you feel proudest of. No time for the ostentation of her peers, no time for mayoral flags to be flying from cars. For the Barbaras of the world, time is designed to be juiced to the rind, for doing what needs to be done, and doing it with all your might. This is the warmth that comes from a blaze.

2) They say that when you really love something or someone, you actually can’t stop talking about it, and subliminally you will always end up back there, because this is the thing or the person that occupies the front of your mind. Every strand of our conversation, whether we’re discussing Monty Python or the top crooks of Sydney’s underworld, eventually meanders back to her children or grandchildren.

Barbara unlatched from the Waverley community and made the move up the Mountain, where she was able to give more time to her family. When interviewed for a Good Weekend piece in 1995, this was still a bit of a pipe dream:

“All my life I’ve done what other people expected me to do or wanted me to do … now I’d like to have a place with a big shed for my lathe and all my stuff and live happily ever after…”. To which the reporter responded: “But was she really thinking of deserting Waverley to live in the mountains, I asked, knowing she wouldn’t”.

How wrong the interviewer was, and how lucky we are for it.

Barbara has never been a tall woman. The scribblings of centimetres on her wall suggest that some of her grandchildren tower over her. But much like the family growth chart, there are visible reminders of Barbara’s past, scattered like fingerprints throughout Waverley. If you find yourself on the headland at North Bondi one day next to the glittering blue belly of the ocean, you’ll look down at the little specks of the backpackers as they stretch out bronzing in the sun. Then you’ll look to your right and catch clusters of art deco brownstone buildings as they ramble down the hill and hug the coastline, and probably still harbour a rusty hills hoist in the patio out the back. When you are drinking all this in, imagine for a moment that your view to the right is blocked by high rise apartments. Then imagine a woman standing in the same spot 20 years prior, imagining the same. Feeling the same sense of loss and anger, then feeling prepared to do something about it.

(1) Wynhausen, E., 1995. Local Authority. Good Weekend

(2) Mitchell, A., 2007. The Last Moments of Juanita Nielsen. [online] The Sydney Morning Herald. Available here

(3) Saffron, A., 2008. Gentle Satan: Growing up with Australia’s Most Notorious Crime Boss. Penguin.

(4) Jacobinmag.com. 2020. Juanita Nielsen Was Murdered for Standing Up to Sydney’s Developers. [online] Available here

(5) Almeida, L. and Trigg, C., 2020. Waverley Council Is Assessing a Proposal to Open an Amalfi-Style Beach Club on Bondi Beach. [online] Broadsheet. Available here [Accessed 12 March 2021].

A huge thank you to Blue Mountains City Council for the Community Assistance Program funding to employ Annabel Pettit to interview our resilient locals!